How To Design Tokenomics: Understanding The Key Pillars

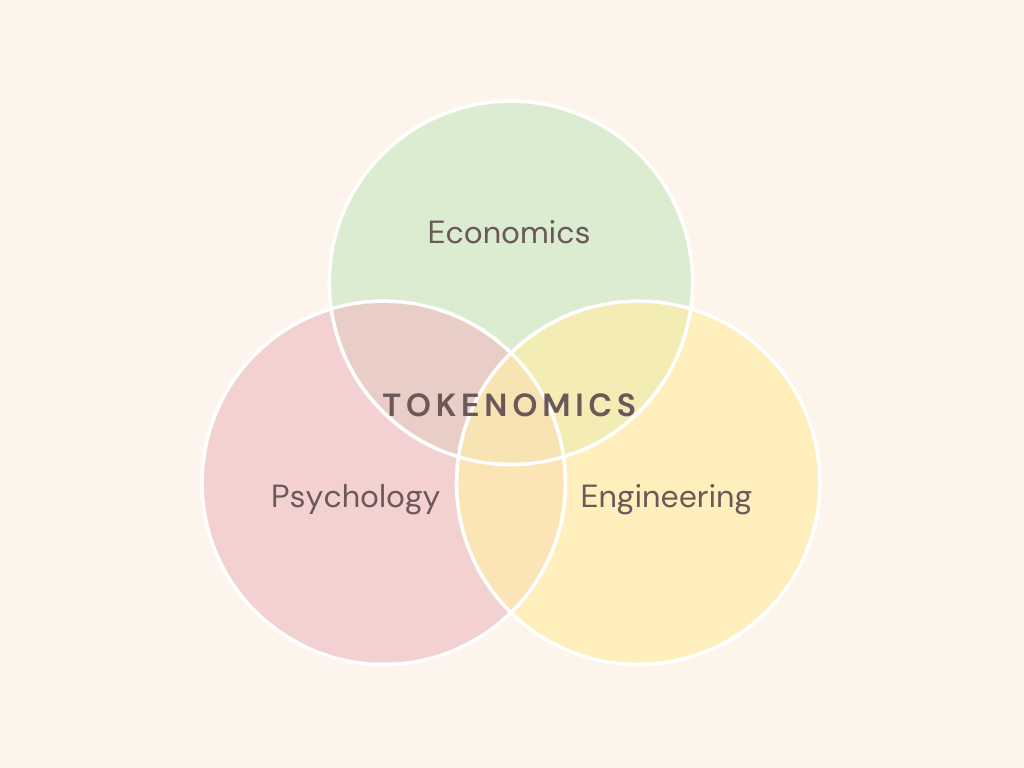

Tokenomics, the economic model behind a blockchain project, plays a crucial role in the overall success of a decentralized network. It not only determines how the network is funded but also how incentives are aligned to encourage good behavior and secure the network through game theoretical concepts.

Game theory is a branch of mathematics that studies strategic decision-making in situations where the outcome depends on the actions of multiple parties. It is, therefore, essential for understanding and predicting the behavior of market participants and the overall dynamics of the network.

A well-designed tokenomics model that takes into account game theoretical concepts can help create an ecosystem that encourages user adoption and engagement.

In this article, we will dive deep into the key pillars of tokenomics and discuss their importance and potential implications for blockchain projects.

Making it right on the Supply Side:

A well-designed token supply mechanism is crucial for the success of any token economy. As a developer or founder, it’s important to carefully consider the supply mechanism of your token to ensure it aligns with the overall goals and vision of the project.

The total supply of a token influences its scarcity, which in turn affects its utility and demand within the network. For instance, a deflationary model that reduces the circulating supply of tokens can increase its scarcity and strengthen its utility within the network. On the other hand, an inflationary model may have a more stimulating effect on the network’s growth and development.

So, the key question here is: Based on the supply dynamics alone, how could you ensure maximum user participation and sustained support?

Let’s find the answers analyzing three different aspects of token supply:

- Allocation

- Vesting

- Emission

Allocation

The distribution of tokens among key parties is referred to as allocation, and it is the fraction of the total supply that each wallet possesses. It is a critical component of tokenomics that developers should consider before making their project live.

A successful allocation design distributes tokens among several persons rather than concentrating them in the hands of one person or organization. It also helps to maintain the project decentralized by preventing any single entity from wielding too much authority over it.

The allocation for the core team, private investors, public sale, ecosystem incentives, treasury allocations and others must be carefully considered.

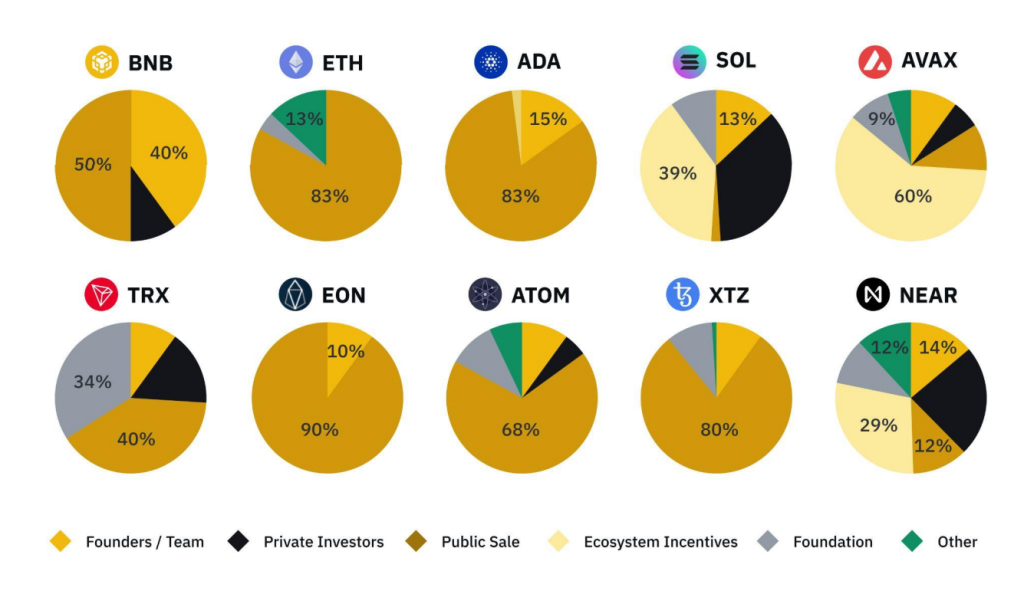

This can be observed easily taking an eye on all the L1 chains available today. L1 chains like AVAX, NEAR protocol that were launched in 2020, have much higher allocation for ecosystem incentives, compared to Ethereum, BNB and ADA that were launched around 2017 or before. .

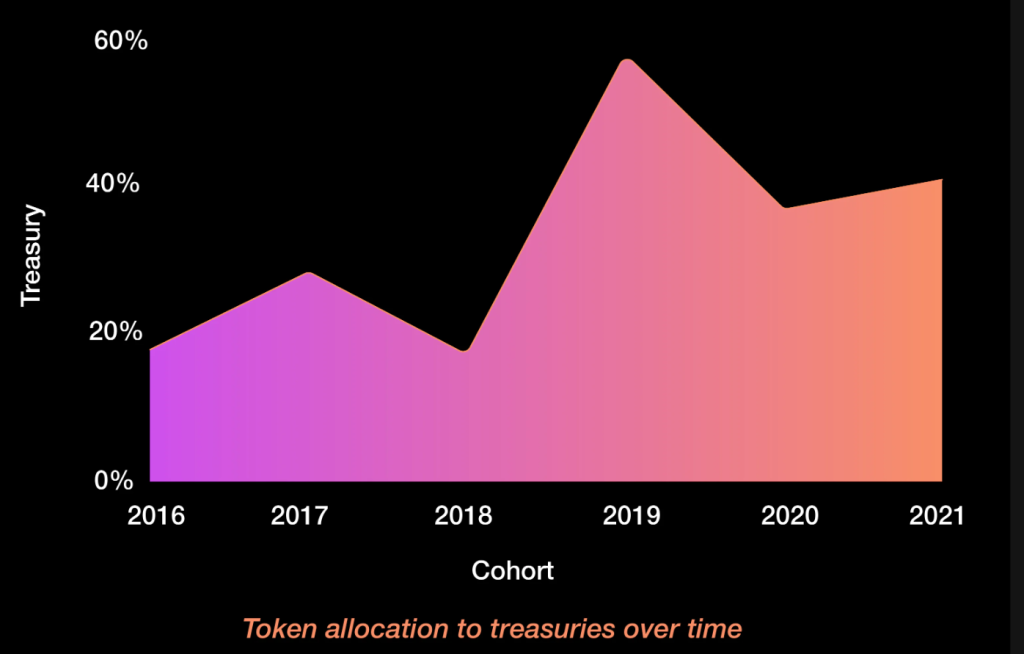

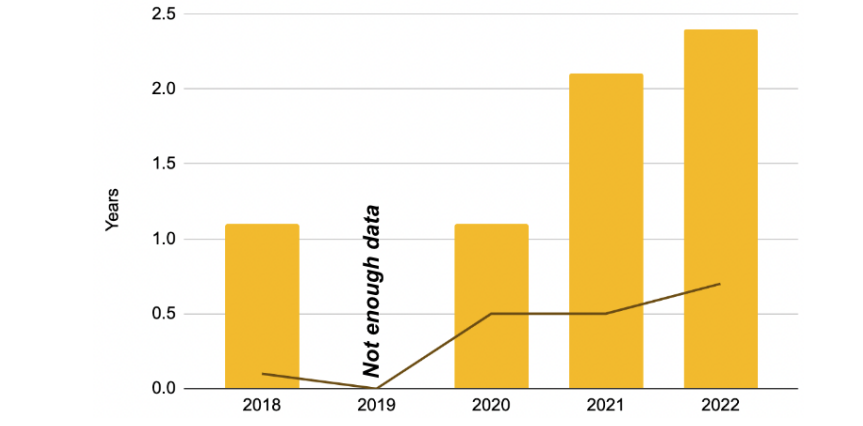

You can also observe public sale allocations are steadily decreasing in most recent years, while allocations for the early network users or adopters are in the increasing side. Developers should also consider allocating a fraction of the total supply to a treasury that can be used for long-term funding and ensure sustainability. The graph below shows the trend of token allocation to projects’ reserve pools from 2016 to 2021.

But a few significant points here needs to be kept in mind:

- For earmarking tokens for founders or foundation, we shouldn’t increase the centralization risk anyway. Because if there is a significant overlap between the core team members and board members, the chances of token getting concentrated in the hands of a few increases.

- To ensure ecosystem incentives are rightly distributed to the genuine adopters, it’s crucial how we plan to distribute tokens. Also there needs to be a balance between how much we distribute now versus how much we are keeping for future incentives.

The earmarking of tokens for more value-accretive purposes makes sense from a protocol perspective and can be an effective way to incentivize market participants to work on improving a product.

Vesting Period:

Vesting is the process of gradually releasing tokens over a predetermined period or until a particular event is triggered, incentivizing stakeholders to hold their tokens for longer rather than selling them immediately.

It also helps the project maintain control over its own token supply while ensuring that investors are rewarded for holding their tokens and contributing to the success of the project. It also helps in maintaining the price of tokens and reduce price fluctuations.

Typically, vesting periods range from several months to several years, and the amount released in each period is usually determined by the project’s tokenomics model.

This way, the token holders will have a ‘vested interest’ in the project’s long-term success. Even the tokenomics can be designed in such a way that more incentives/ discounts are offered for tokens with higher-lockups. An example of this could be ‘File Coin’. They offered higher discounts to investors in the private and public sale round who choose vesting period from 6 months and upto 3 years.

In the recent times, it’s observed that projects are going for a higher lock up periods (or vesting) and cliff lengths.

‘Cliff Length’ is the time when no tokens are released. This could be different for different types of investors. For pre-seed or seed round investors it could be 3 years, where for public round investors it could be 6 months. For founders the cliff length will be different also. And after this cliff length is over, the token release starts with linear or graded vesting attached with it.

But here also the architect of the tokenomics needs to maintain a balance. The tokens in circulation needs to enough to ensure operations can run smooth as they should.

Emission & Burn:

The regular issuance of new tokens into the circulating supply is known as emission, while removing of tokens from the supply is called ‘Burn’. It helps ensure that the network remains liquid and accessible to users without any disruption in service.

Emission and burn rate can vary greatly depending on the project’s goals and objectives, but it should be carefully considered before a tokenomics model is established as it can affect liquidity, adoption and security.

High emission rates (inflationary tokenomics) could cause centralization for projects that are growing at a relatively slower pace. It could also increase the incentives for attackers to compromise the network. On the other hand, high token burn rate (deflationray tokenomics) could cause liquidity issue in the future when adoption increases.

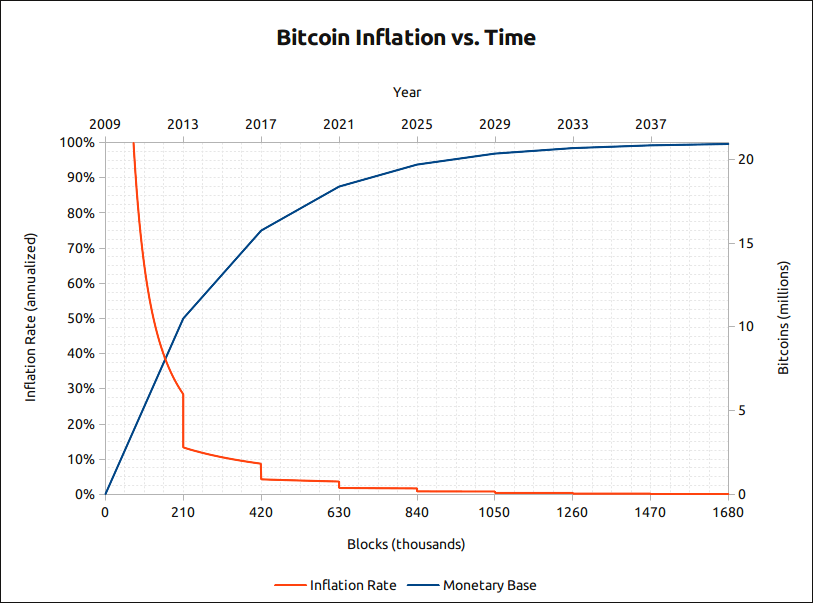

Most projects start of with a higher emission rate and gradually decrease. An example can be seen in the case of BTC. Although Bitcoin is designed to be a deflationary currency in the long term, with a fixed maximum supply of 21 million coins, it can also be considered inflationary in the short term due to its emission rate.

Point to note here is that, a project can employ both inflationary and deflationary mechanism into its tokenomics. And the demand and supply of the tokens controls emission or burning of tokens.

Rewards in the form of emissions are typically allocated through block rewards, which are given to miners or validators who play a crucial role in securing the blockchain network. Alongside this, some projects may also opt for issuing tokens specifically for ecosystem incentives or strategic partnerships to foster growth. Moreover, emissions can also arise from transaction fees, which can either be burned as a form of removal from circulation or rewarded to validators. These mechanisms may be combined, depending on the specific implementation and design of the token ecosystem.

Depending on the level of network usage, if a significant amount of tokens is continually burned, it has the potential to counterbalance the inflationary impact of block rewards, leading to deflationary pressure on the token. Both BNB and Ethereum show this effect happening at the same time.

Airdrop & Lockdrop:

Airdrop is a process of distributing tokens to early believers or even existing holders of a specific crypto, for example, it could be Bitcoin or Ethereum. Take the Aptos airdrop for example. In it, the project distributed its tokens to holders of ETH, BTC, and a few other cryptocurrencies. As a result, the Ethereum and Bitcoin community, which are the two largest communities in this space, started talking about $APT and the project got some good attention.

Airdrops can create a community of token holders and generate awareness for a project. But more than that, airdrops are an excellent way to decentralize the project by spreading out the tokens.

One of the challenges associated with this method is the presence of users who try to “game” the system and exploit airdrops by farming them. A recent prominent instance is the Arbitrum Airdrop, wherein 10 million $ARB tokens were distributed based on users’ chain activity. However, rumors suggest that only a small group of individuals successfully obtained all the tokens by deceiving their on-chain activity using numerous wallet addresses.

In the event that these Sybil attackers manage to acquire a disproportionate share of the token allocation, it can have detrimental effects on a protocol, particularly when governance matters are at stake or when there is a risk of price dumps.

Now, let’s explore an alternative approach known as Lockdrop. In this method, instead of relying on past activity to allocate tokens, the project considers future commitments. For example, the project team can set criteria such as holding Ethereum for a specific duration to receive a specific amount of their token as a reward. The longer Ethereum is locked up, the larger the share of the project’s token. Moreover, the team can introduce additional incentives by putting those tokens into a liquidity pool and earning further rewards on them. This approach fosters the growth of an engaged community.

As a developer or project founder, you have the ability to choose which kind of distribution method makes more sense to you. That way you have a good starting point without letting go of control and also a reliable to lower centralization risk.

The Demand side of the equation:

The demand for tokens can be determined by the number of active users, holders, and transactions in the network. The demand for a token is driven by its utility and incentivization structure, which can increase or decrease depending on the project’s success.

An example of this is seen in the case of Ethereum (ETH). Over the years, Ethereum has cemented its place as one of the most popular blockchain networks in the world. This is mainly due to its utility and wide range of applications, such as smart contracts and decentralized finance (DeFi) protocols. The demand for Ethereum has grown significantly over the years, resulting in more people joining the community and contributing to the project.

Therefore, when designing the tokenomics of your project, need to implement strategies and mechanisms that would drive up demand and invite more people to contribute.

Without demand supply would be of no value. To generate demand, we need to fix

- Utility of tokens

- Governance of projects

- Different approaches to share revenues

Utility

Utility is the foundation for mass adoption and longevity for any project. While many have garnered a lot of attention without much utility, it is not a sustainable model.

The goal here is to create a token that has real-world utility and can be used for multiple purposes within the ecosystem. It is crucial for utility to be tightly linked to the core business model, and must be designed in such a way that it encourage use of that protocol.

Lets take a look at ChainLink. LINK, the project token, is used to compensate Chainlink Node operators for retrieving data from external data sources, turning it into a blockchain readable format. Node operators offer off-chain computation and uptime guarantees. For example, if a company wants to use a smart contract together with a Chainlink node, they can do so with LINK tokens only.

The utility of a token should be visible in its use cases, such as incentivizing users or rewarding them for their contributions, providing access to services.

Utility tokens can be used to access a certain service or feature, such as DAI which is used as collateral in MakerDAO, or Binance Coin (BNB) which is used to transact on the Binance Chain.

Revenue Sharing

Many projects offer rewards and incentives from its revenue to token holders in order to drive demand for their tokens. This could be done in two ways mostly.

- On-chain, when a network executes an action, a small fee is collected and subsequently distributed to token holders periodically.

- The ‘Buy and Burn’ mechanism functions by utilizing the fees generated from on-chain actions to purchase tokens from the market and permanently remove them from circulation. This intentional reduction of the circulating supply aims to enhance the scarcity of the remaining tokens, potentially leading to an increase in their value.

These revenues could be shared among the token holders, liquidity providers, and also for the operation of a DAO, but not in equal share. Like, Uniswap shares 100% of its revenue to Liquidity providers. Curve Finance has a 50%, 50% revenue share between Liquidity provider and token holders. Similarly, Pancakeswap, Sushiswap has their own proportion for sharing revenues between multiple stakeholders.

Governance

The third factor determining demand is governance. Having a native token for your project holds significant value as it allows for effective protocol governance. It not only differentiates various protocols but also provides a layer of security and reassurance to the community.

Tokens can be used to vote on proposals to change the ecosystem. The more tokens a holder has, the more influence they have in the governance process. This idea follows ‘one coin,one vote system’. One of the earliest adopters of this model was Maker DAO. They introduced a governance system where every MKR token equals one vote and the decision with the highest votes win a proposal.

Another example of this model could be $COMP of COMPOUND. You get COMP based on your on-chain activity. The more you lend and borrow on Compound, the more COMP tokens you receive. Similar to MakerDAO, one COMP token equals one vote.

Notably, in 2020, Compound relinquished control of the network’s admin key, allowing the project to be governed solely by its token holders without any alternative governance methods. This approach, known as progressive decentralization, involves the gradual transfer of governance power to the token holders over time.

However, the ‘one token, one vote’ model has inherent drawbacks, as it fails to reward good decision-making compared to poor decisions.

As an alternative, a second model known as the ‘Vote Escrow’ model has gained popularity in recent years. This model grants higher voting power to tokens that are locked for a certain period, thereby disproportionately rewarding long-term holders. Curve.finance serves as an example of a project implementing this model.

Conclusion

Tokenomics plays a crucial role in the success of any project. A well-designed tokenomics model can lead to a successful and valuable token. In contrast, a poorly designed model can result in a token that is not widely adopted or valued.

Understanding the key pillars of tokenomics is crucial for understanding the success and value of a token. This is a rapidly evolving field, and having a solid understanding of it can help you stay informed about the latest developments and trends in the industry, evaluate building opportunities, and identify new facets of innovation and growth.

Building your own project? Need access to top L1, L2s or appchains? Visit Zeeve today, and start your Blockchain journey.

Responses